Bycatch paper published in Science

A paper that I co-led with my good friend and frequent collaborator, Matt Burgess, has just been published in Science:

”Protecting marine mammals, turtles, and birds by rebuilding global fisheries.”

This is the culmination of a lot of work over the last 18+ months. It was also a true interdisciplinary effort, involving a great team from a variety of backgrounds (economists, ecologists, conservation scientists, etc.). I’ve already tried to summarise the main contribution of the paper on Twitter and highlighted some of my favourite aspects. But here’s a blog post for those of you aren’t masochists on social media.

(A quick clarification on definitions first for anyone who isn’t familiar with this literature: “Target stocks” refers to economically valuable fish stocks, like tuna, that are typically caught for human consumption. “Bycatch”, on the other hand, refers to unintended fisheries catch, like turtles or dolphins getting caught in tuna nets.)

The paper is about an important collateral benefit of reforming global fisheries. Namely, how many threatened bycatch species would we save in the process?

It turns out that the answer to this question is “quite a lot!”

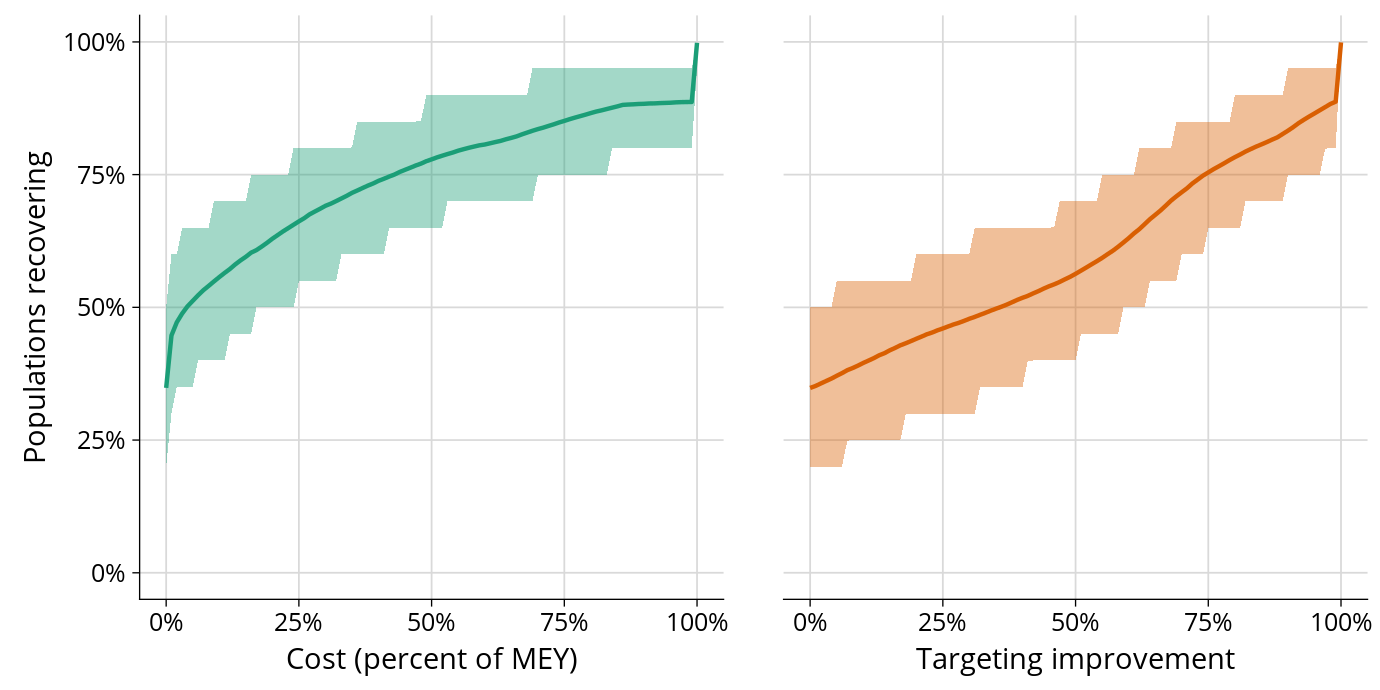

We estimate that approximately half of these threatened bycatch species could be saved by reforming target fisheries in a way that maximizes long-term profits. Below is the key summary figure from the paper. The left-hand panel shows the fraction of threatened bycatch populations recovering at different cost levels (defined in terms of foregone profit in the relevant target fisheries). The solid green line denotes our mean estimate and the shaded green region denotes a 95% probability interval. Again, we can see that approximately half of the threatened bycatch populations start recovering at minor (<5%) loss to the maximum profits of target fisheries. The right-hand panel shows the same thing, expressed in terms of targeting improvement (e.g. how much better tuna vessels need to get at catching only tuna instead of turtles or dolphins).

At its heart, this paper is really a classic environmental economics question about negative externalities and spillover effects. If we fix one problem (unsustainable fishing), can we solve another (threatened bycatch species)? And, while the paper would have been impossible to complete without pulling in experts from a variety of fields, that core idea is what appealed to me as an environmental economist when Matt first proposed it.

There are a couple of other fundamental economic ideas that I’m very pleased to have incorporated into our analysis. For example, we’ve taken pains to ensure that foregone profits are calculated according to principles of economic efficiency. If a bycatch species (say, the E. Pacific leatherback turtle) requires additional reductions in fishing – i.e. beyond those dictated by the goal of maximising long-term profitability – then we don’t just assume that those reductions will be uniformly distributed among its various target fisheries (say, a mix of tuna and other demersal fisheries). Instead, we ask: “Where is it cheapest to reduce the next unit of fishing activity?” By ordering things in terms of marginal fishing costs, we ensure that we achieve our end conservation goal at the lowest possible cost.

I’ll highlight two final aspects of the paper before closing.

The first is the extent to which we’ve tried to account for and even embrace multiple forms of uncertainty; every estimate and parameter in the paper has an explicit distribution attached to it. There are a lot of unknowns about fisheries bycatch. We wish we knew more. However, the reassuring – and potentially surprising – thing is just how robust our central finding is to these various forms of uncertainty and a raft of sensitivity tests.

Second, I’m proud of the efforts that we’ve taken to scrupulously document our work and make it available to others. Matt and I, together with the rest of our coauthors, are big supporters of scientific transparency and reproducibility. All of our analysis, R code and data is available on GitHub. If you were so inclined, though I don’t recommend it, you can even dig through our long commit history to see how we problem-solved and arrived at the final product. For example, here’s me mildly berating Matt after I discovered some well-hidden for-loops that were causing frustrating timeout issues and other problems. (Remember kids, avoid for-loops in R!)

That about covers it. I hope you enjoy reading the paper. Please feel free to play around with the code too. And a final caveat: One person’s bycatch might be another person’s lunch. As I discovered in an Egyptian supermarket some years ago…

PS – Some nice coverage of our paper in Science Daily, Around the O, the EDF blog, and European Scientist.

Comments