Changing Faces

Saracens have earned plaudits — as well as attracted a degree of professional acrimony and jealousy — for

I went along as a guest to one such session this weekend, which was led by James Partridge, founder of Changing Faces. As the name implies, Changing Faces is a charity that "supports and represents people who have disfigurements to the face, hand or body from any cause".

James' own life was forever altered after being involved in a severe care accident in his late teens:

On the Ides of March 1971 (15.3.71), I looked in a mirror for the first time after my accident 3 months previously – and from knowing myself as a good-looking 18-year-old guy with prospects, I came face-to-face with a disaster area which, it was very hard not to think, could only hold a very tarnished and unhappy self.Interacting with everyone at the club, James was never less than charming and confident. Alongside a genuine interest in other people, it's amazing what a difference those qualities make towards disarming any knee-jerk reactions to his "strange face" (as he put it). There was no need for avoidance of eye contact, unnatural sympathy, and so forth, simply because he appeared so comfortable with himself and effectively managed the expectations of others.

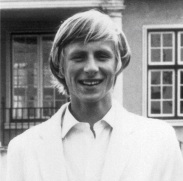

The photo tells only a part of the story because (a) it is black-and-white, and (b) it was taken two months after my day of reckoning when my face was still bloody scabs, vivid redness, and ghastly distortion.

Look carefully and you may see the tell-tale signs of doubt, grief and pessimism – I felt all of these as I scanned across that face and I just could not imagine how I could ever get my life back – any kind of life, frankly…

Five years of brilliant 1970s surgery created the face I now wear with pride but it was what went on outside hospital as I struggled to become a fully-included citizen and not an outsider, a horror-movie villain nor a just a lifelong patient, that really counted for me.

|

| James as he is today |

Listening to his story, I was also reminded of Vanilla Sky. In addition to a great soundtrack, I admired the film for seriously tackling the issue of how our physical appearance is intrinsically linked to our happiness; a subject that is too often passed off as frivolous and vainglorious, when of course it isn't. I'm used to interacting with the world in a certain way and much of that is contingent on the way that I look. In fact, I'd venture that we all trade on our looks to some extent and, as Oscar Wilde observed, beauty is its own form of genius.

Unfortunately, in Vanilla Sky Hollywood sensitivities ultimately won the battle: A disfigured Tom Cruise sees all his problems solved via cryogenic freezing and a visit to an advanced plastic surgeon's office at some unspecified point in the future. (Talk about realistic expectations!) In contrast, the people at Changing Faces offer some real insight into how those with disfigurements can overcome the challenges of integrating into a society obsessed with looks.

Comments